A Storyteller's Calendar

(Nho Quế River, Vietnam, June)

I set out from my dreary hotel room like a bushwalker. I would walk no fewer kilometres that day than I would on a long loop hike, though the footpaths were overcrowded and air cloying and humid. I strode past an ice-cream place, a soup stall, and a young boy selling flowers from a wheelbarrow before I even got to the first street corner.

After some hours on hoof, I came upon the shores of a lake and saw the familiar shapes of squabbling birds. They occupied the tangled branches of grand figs that choked an island, interlocked so that they formed a deep and gripping bower. Hidden within that, I realised as I entered the green shadow, was a Buddhist temple – which doubled as a bird-hide as the bitterns and kingfishers took positions in the shadows, emerging to scour the dirty water for prey.

In the temple, there was a replica

of a long-legged bird, standing on the shell of a tortoise,

pressing it into the ground. In its beak

the fowl held a bead, or marble, or gem.

For me the sight of a bird is itself a pearl of great price.

I sat there for hours, until I was jostled out by a group of elderly local woman, who did not appear thrilled to have a stranger in their midst. Through the streets of Hanoi, I carried on bushwalking.

(South Coast Track, Tas., March)

(Melbourne, Vic., October)

It is good to be forced into a different version of yourself, to see yourself as an other and an outsider. Even so, sometimes I catch the sudden rush of energy that comes from being around so many other people, and anonymous. One afternoon – perhaps enabled by a particularly good plate of fried rice – I approached a pair, two strangers, sitting on some outdoor furniture and asked if I could take their portrait. “Cool style,” we agreed.

I felt the surge of exhilaration, too, one day in Melbourne. There are few places through which I have strode more miles. Left alone in that flat, broad city, I will stretch my legs and jot countless notes in my journal. On this occasion, I was in need of a new one of these notebooks: so I walked in the direction of a store that sold office and art supplies until, at its doorstep, I realised that I had gone to the very same warehouse that had nothing on its shelves a few days earlier.

My time in Melbourne is like this: journeys that circle in on themselves, memory folded into memory. But I was playing out stories in my head, practising a speech and plotting verses for an upcoming gig. Sometimes in cities, walking around in a stunned state, agog. Often enough, I am elsewhere: in the past or in the yarns I am told by my good friends there. (There is a bend in the road near in the inner north where I now find myself, in fact, in a square in Zagreb, looking over a memorial statue, melding into a second-hand account.)

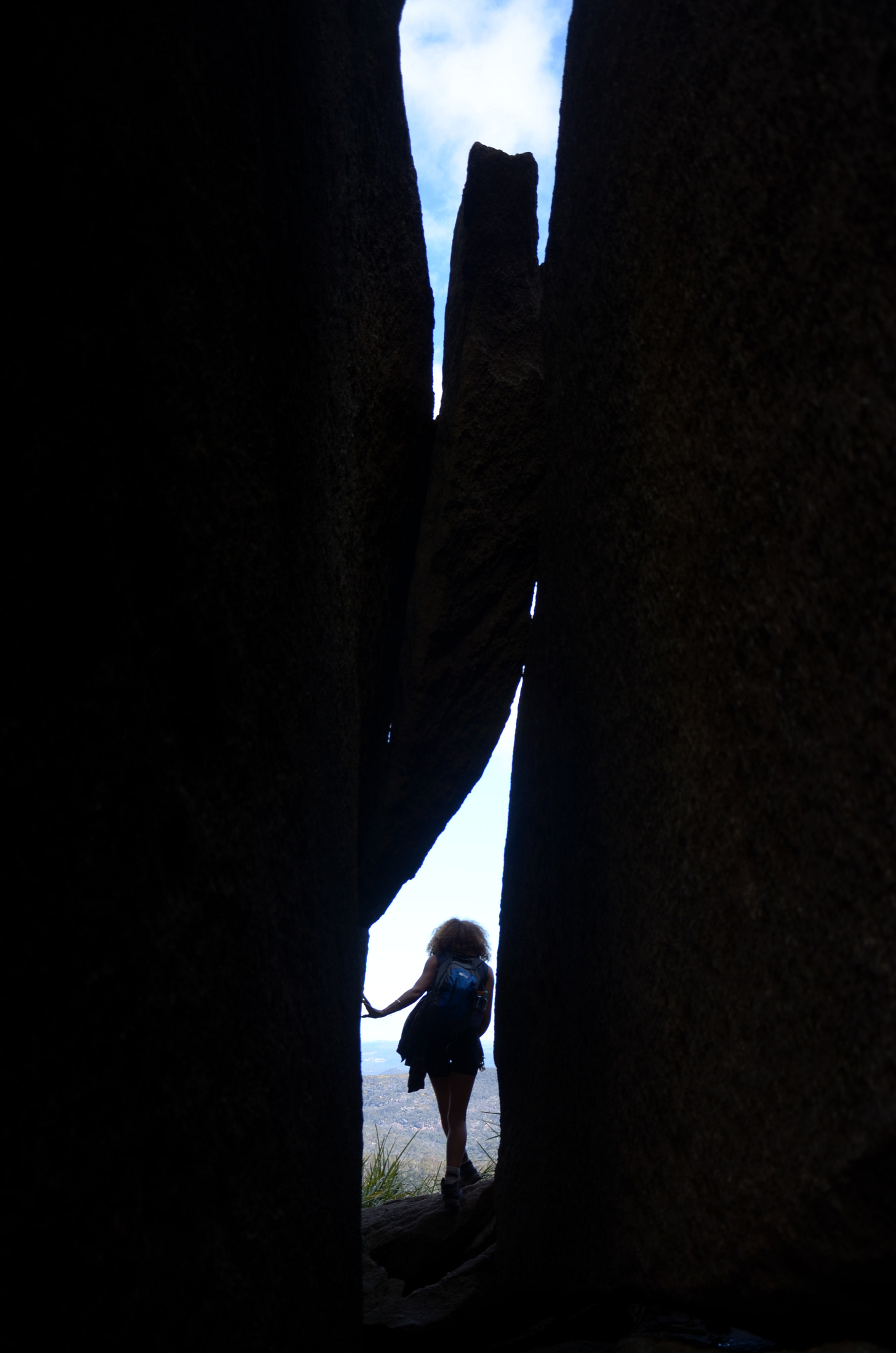

(Glass House Mountains, QLD., April)

(Girraween, QLD., August)

I arrived for a poetry reading in a Melbourne hotel and was told that the venue would be turned into apartment blocks before the year was out. The same thing had happened to me in Brisbane too. Cities are cruel; they show no care for our memories of place. There is no regard for the fact that humans build identities on habitat, that we have done so forever. We must strike out to the bush, where it all moves much slower.

It is good to make acquaintances with new places, different geology, an array of birds. For some days I woke to the astonishing light on a hill in south-east Queensland

where mornings have a long span, through both space and time.

The sun ascends the distant shadow-green spur and pours colour

into the valley, and then he strolls across the open dale.

Not till evening does he climb over the hills behind us,

beyond the hinterland and into the neighbouring people’s plains.

There I heard the story of a surfer, who – with his partner – had spent his last dollar on a paddock, a former papaya farm that was filled with rocks, leftovers from an abandoned mine. If life gives you lemons: the man was a stonemason and so took the local trachite and turned it into a cottage. It was in this that I woke up.

(Overland Track, Tas., May)

(The Tarkine, Tas., March)

Not far from there, I walked alone in a woodland reserve, wedged in between roads, lanes of cracked and sticky bitumen that urged traffic to rush between villages. The reserve itself was an afterthought, protected by virtue of the fact that no-one wanted it. There were more majestic forests than that in the district, but I was drawn to the gravel trail through those cabbage tree palms, ironbarks and blackbutts.

Restless rufous fantails cavorted between shrubs; golden orb spiders dangled over the path; fruit-doves, as heavy as pears, could be found along branches. I liked it because it was full of life, and because I was there.

I came upon a small body of water and sat there for a long while. It was grey-green and opaque, stirred by insects: the friable green scales on the surface might have been mixed into the liquid, dissolved as completely as salt. The pond had no role in myth or folklore, and there was nothing in particular that I waited for as I squatted beside it. I wrote:

There are no spirits or monsters that I’d like to call forth,

no torment that I wish to plunge into the depths.

I have no plans to baptise anyone here, to cleanse myself –

you wouldn’t to wash in this sludge after all.

It’s a week in which I have found it hard to pin down thoughts,

to match my rhythm with my mind’s, or with the world’s.

But I know that as I slow down, synchronisation will occur:

this pond’s as good a source of daydreams as anything, anywhere.

Everywhere is special; all places can prompt a new dream.

(South-West Tas., January)

(Noosa River, Qld., April)

I went here and there this year, but mostly I was at home. In an existence with little continuity – a purposeful choice – I am pleased that I have been able to stow my books and rest my head in the same spot for a decent sequence of years now. It is peculiar, always, to reach a poignant date, such as the solstice, and look back on the last of them to see what’s changed.

It is both much and little. Sticking to the same abode for so long, you start to see the richness in repetition, as a steady rhythm upon which improvisation can occur.

There is always need to sweep the hut

once more, and once again.

Debris of every sort is brought in

upon the soles of my feet,

dust and leaf litter, ash and moss,

knots of hair, seed pods,

insects’ discarded husks…

(Train Carriage, Tas., November)

On my wall there is no calendar; I keep track of the passage of time through memory alone. I am not only thinking of future dates. Flexing memory’s muscles, I recall calendars in retrospect, associating events with places. It is a bit like the ‘memory palace’, the mnemonic technique in which you tour the rooms of a mansion where you have stowed prompts for whatever it is you wish to remember.

I have not a palace but a large landscape in my head, a mosaic of moors and forests through which a rough pad passes. There are contiguous countries; sometimes, as on certain long-distance routes, the path passes through a town or city, where I might buy provisions, but carry on again into the bush, binoculars and hand lens at the ready, to look at insects or fungi or feathered creatures.

It has been a year of learning, of listening, of understanding – and above all, for the majority of these twelve months I have paid great attention to writing, not only scribbling more pages than I have before but giving the words a terrific amount of care. Even this work, however, has been situated in real places, stories again infused with one another.

I will long remember typing up notes about Tasmanian geology as I sat, on a damp day in the highlands of northern Vietnam, watching a large tan butterfly – a ‘common cruiser’ – nibbling on the exposed fruit of a banana with skin bent and split.

A long series of meandering candid musings, Bert; much appreciated, and re-read. Thank you.