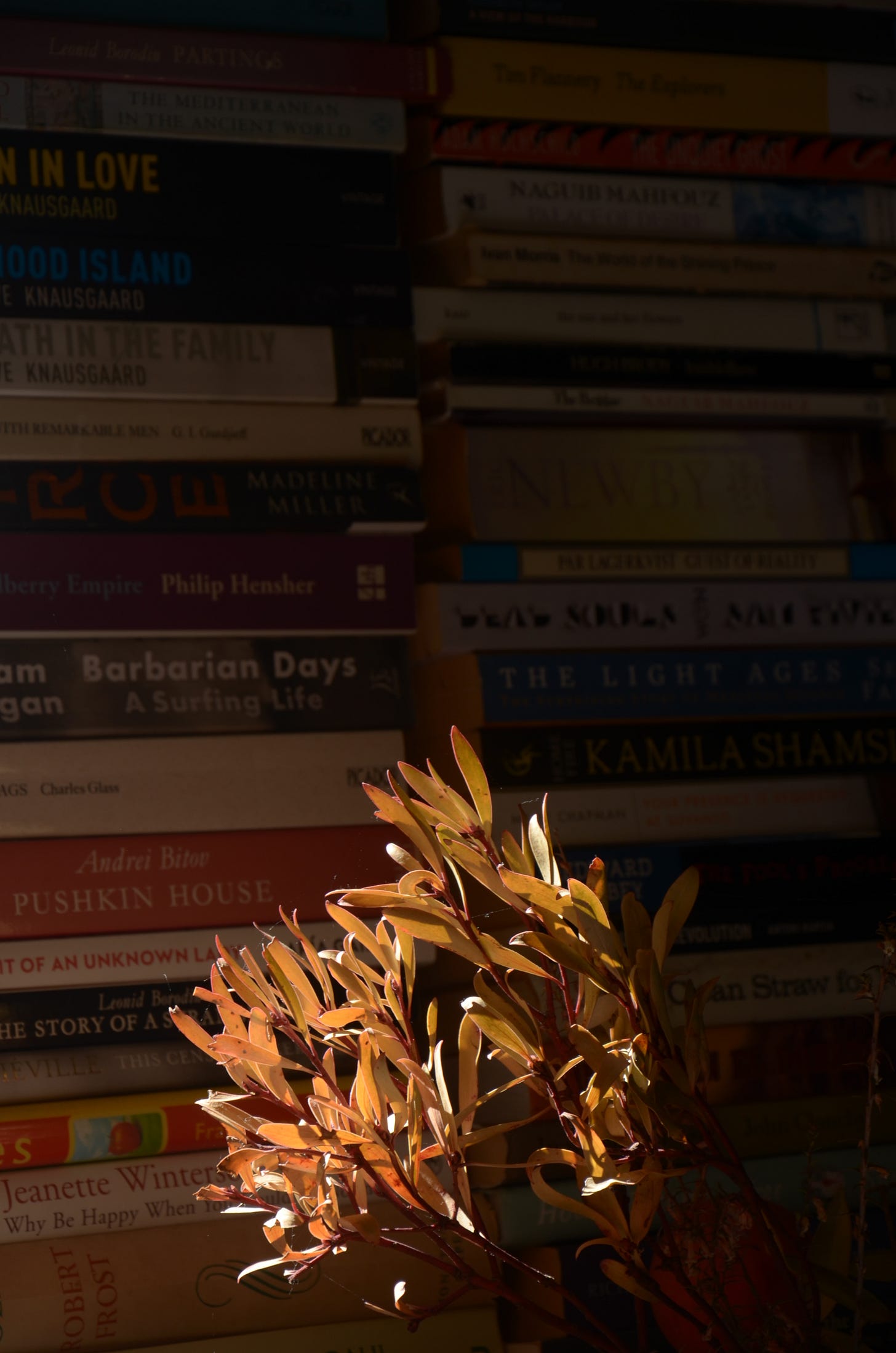

I’m coming to the end of the shortest overseas trip I’ve made in a long while. The grand sum of my time away is six weeks. Above all the things I might miss, it is the eclectic library that I keep in an old train carriage in the Tasmanian bush that has been the most apparent.

A mere six weeks. You’d think I could manage but given the nature of this trip, I’ve travelled light. I didn’t lug the whole kit and caboodle over here, as I normally would – no tent or sleeping-bag, only a couple changes of clothes and a small selection of literature. Just a handful of books.

I actually bought one of them in Melbourne on my way out of the country, which was just as well, because I quickly got to the bottom of my pile.

A fortnight into the journey, I arrived in a new place and asked the guesthouse manager if there was a bookstore in town. A worried look came over her face. No, she said, but – eager to please – she knew someone who had studied in Singapore. Perhaps he had something he could lend me?

The next day my helpful host knocked on the door of my room. She was looking up at me optimistically, holding an enormous tome. I squinted at the title: it was a thousand-page manual about machine learning.

I passed up the offer. I was not that desperate – not yet.

I know, I know. There are other ways to do it. You get a little machine that converts the books into binary code and store the treasured words in there. Somehow your whole library weighs a couple hundred grams. It slips simply into your backpack and you don’t have to worry about it getting dog-eared.

No-one who has met me will be surprised that I am not that keen on that method. I like everything about physical books, particularly when they’re bought second-hand. It’s not just the price: I appreciate the pursuit of particular authors, the thrill of good fortune that is felt when your eyes lands on a certain title in an on op-shop shelf. Then there’s the smell of the pages, markings and stains and marginalia – the little scribbles that previous owners have added to the printed text (though sometimes they are a distraction).

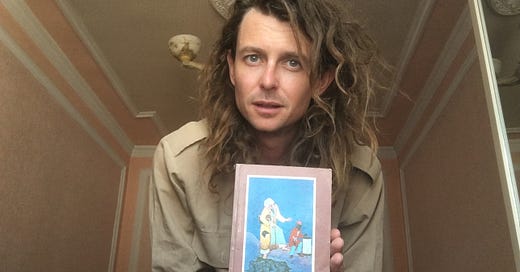

So I keep adding to the weight of my burdensome backpack. In fact, I am even prone to encumbering myself further with books that I can’t even read. These are usually editions that I value for their aesthetic appearance rather than their inscrutable content, or else they are a literary souvenir, a book that is somehow associated with a memory or with some aspects of the country that I have passed through.

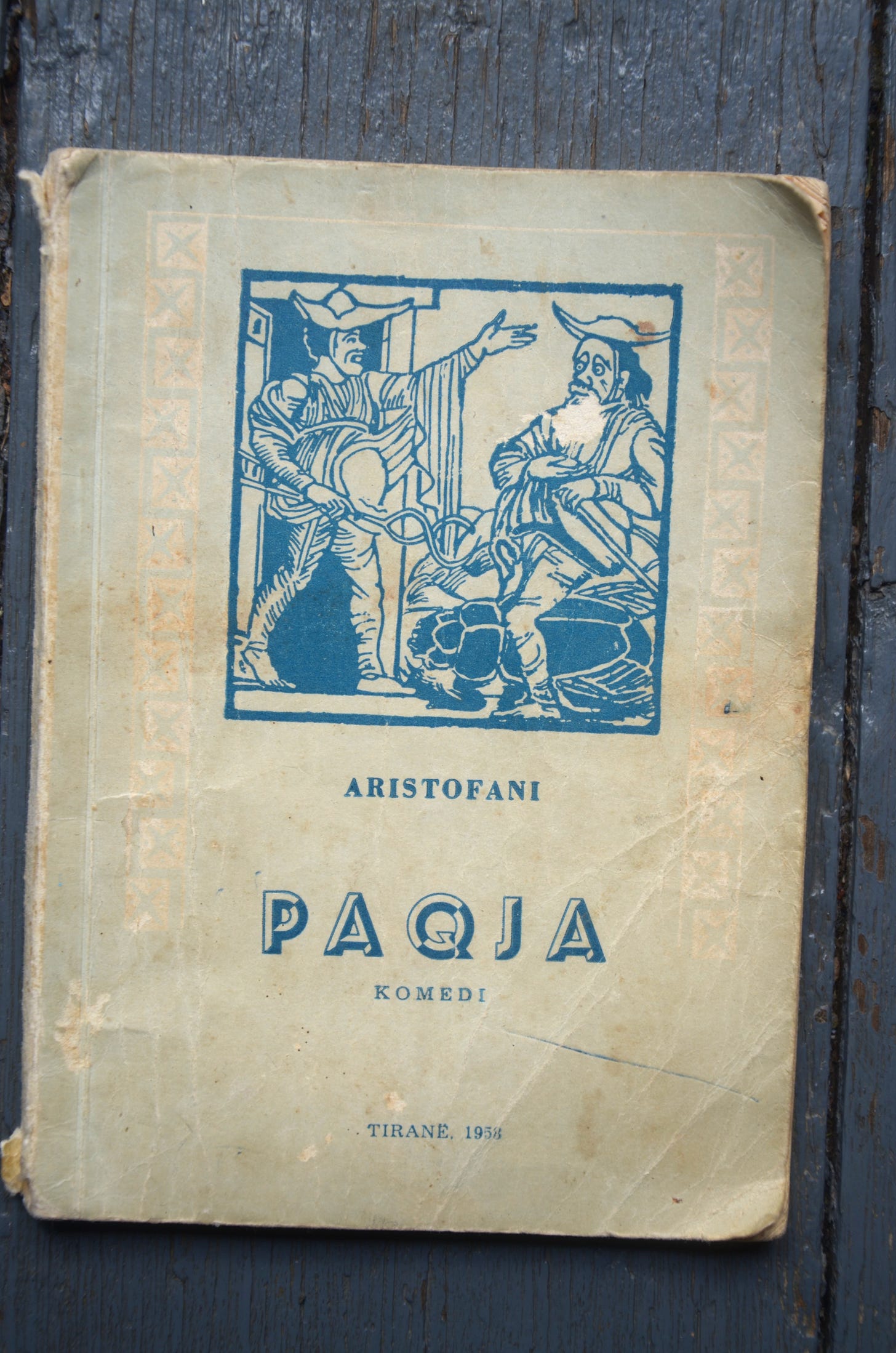

For instance, I had delved into a study of the Greek playwright Aristophanes before travelling to southern Europe in 2022. I hadn’t found any of his works in his own language but at a stall on the street in Tirana, Albania, I found a translation of Peace. A translation into Shqip, that is – the Albanian language, which as you may have guessed, is not one that I have up my sleeve. But it was a pretty copy.

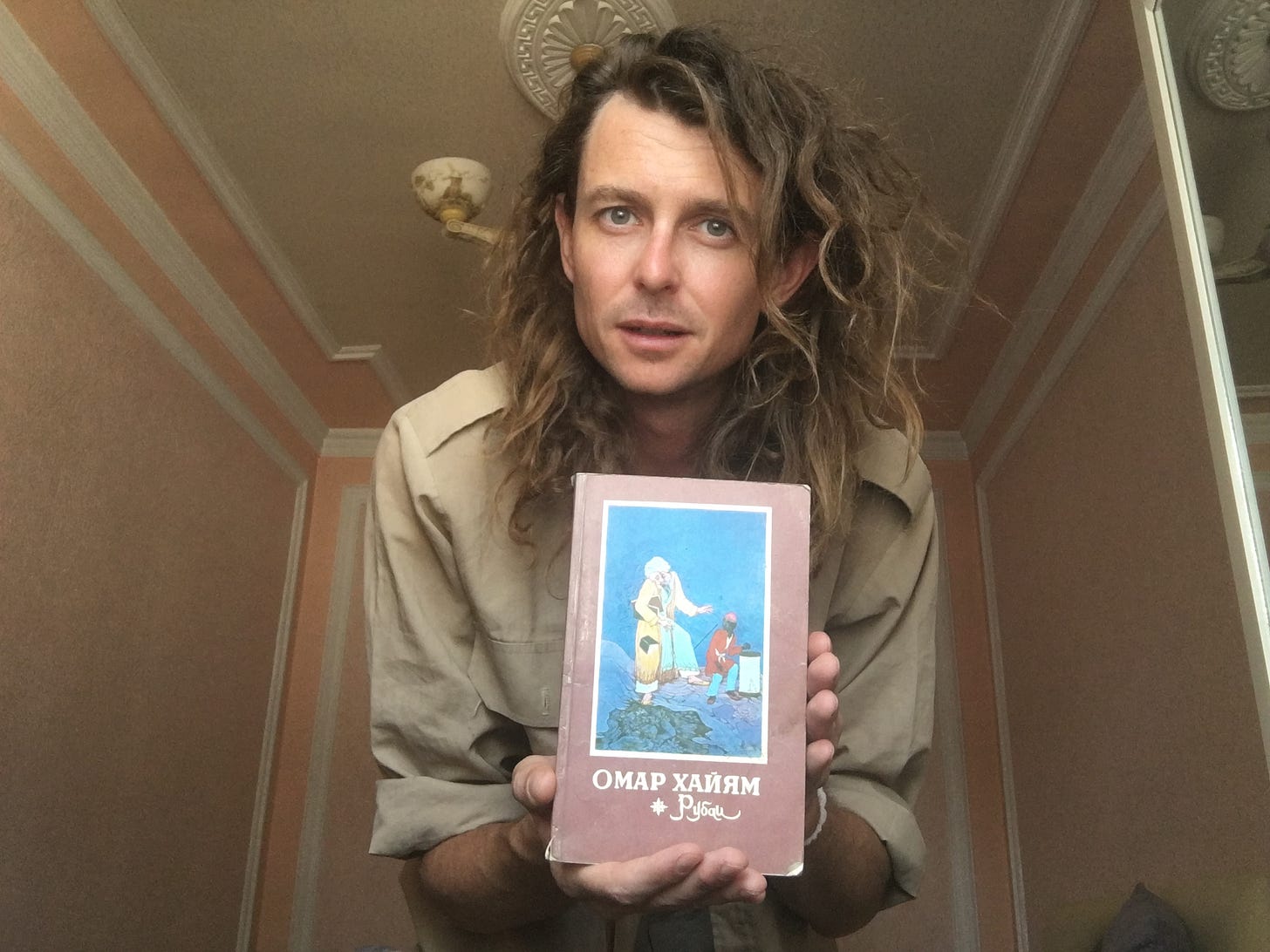

Last year in Uzbekistan, I perused the piles of a used bookstall in the Chorsu Bozor, a big market in Tashkent. The diminutive vendor, a wizened woman who might have been about 70 years old, followed me around spruiking her books with endorsements in Russian. Her book collection was largely in Russian, although some of it was in Uzbek. None of it was in English.

I also don’t read Russian. I mean, I can read the letters of the Cyrillic alphabet and I have a vocabulary of maybe fifty words, but that doesn’t cover a lot of territory. Which is a shame, because there is a lot of great literature that has been produced in the Russian language. But I ended up picking up a little book of poetry. It was a Russian translation of the Persian verses of Omar Khayyam, who some hundreds of years ago lived within the borders of what is now Uzbekistan.

None of this made me a likely customer for this book. But I have a long fascination with Omar Khayyam; I had enjoyed wandering around thinking of his presence in Samarkand. It was a nice coincidence to find him in the pile and the battered edition I was about to buy was, besides, very cheap.

On top of that, the woman selling his work had praised him with her own encouraging comments. I could only understand one word of it. “Mir,” she said, meaning ‘world’. I took it to mean that Omar Khayyam was a writer for all the world, with which I agreed.

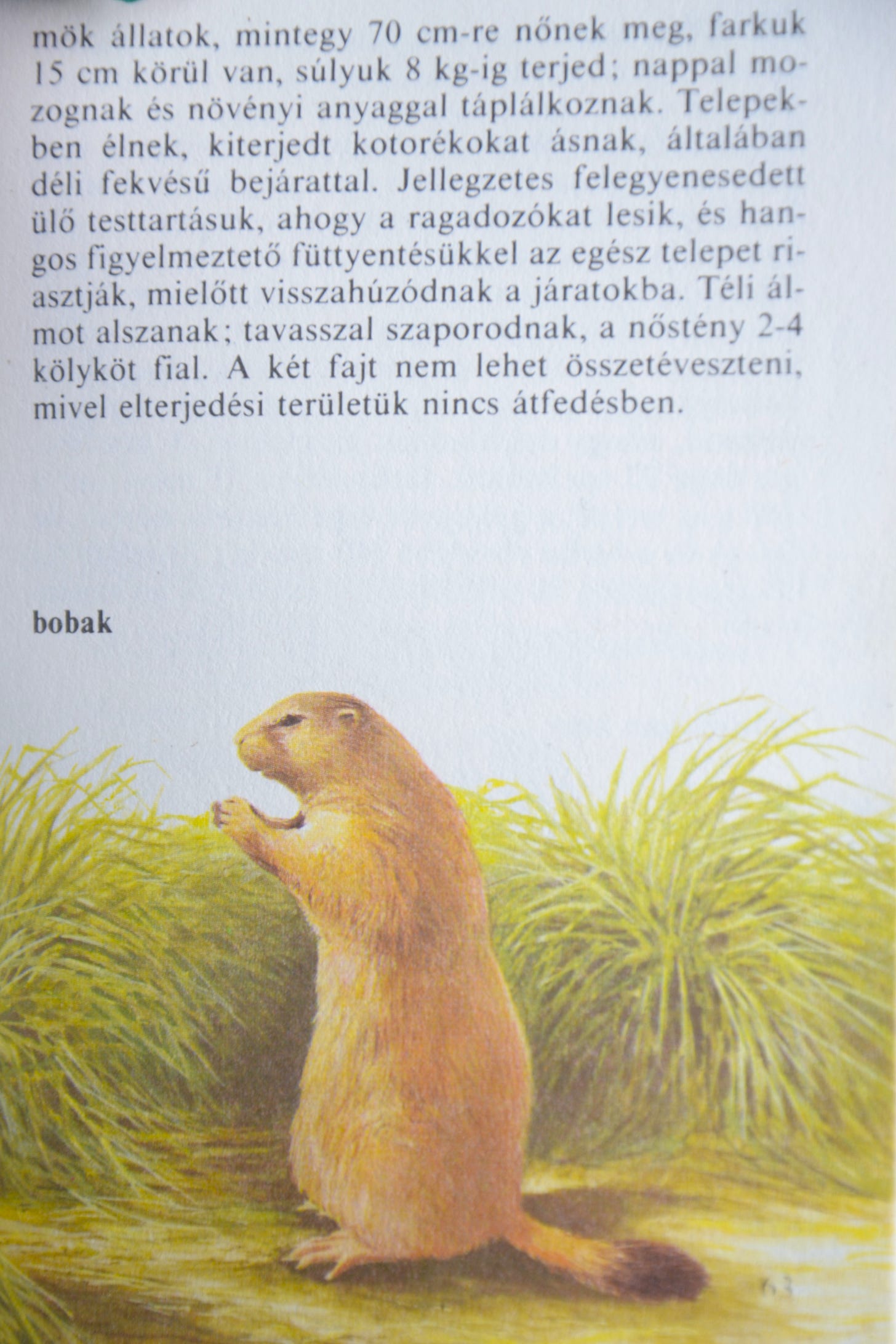

Then there are pictures books. In Budapest, I bought a little field guide of mammals – how else was I going to learn how to say rabbit or marmot in Magyar?

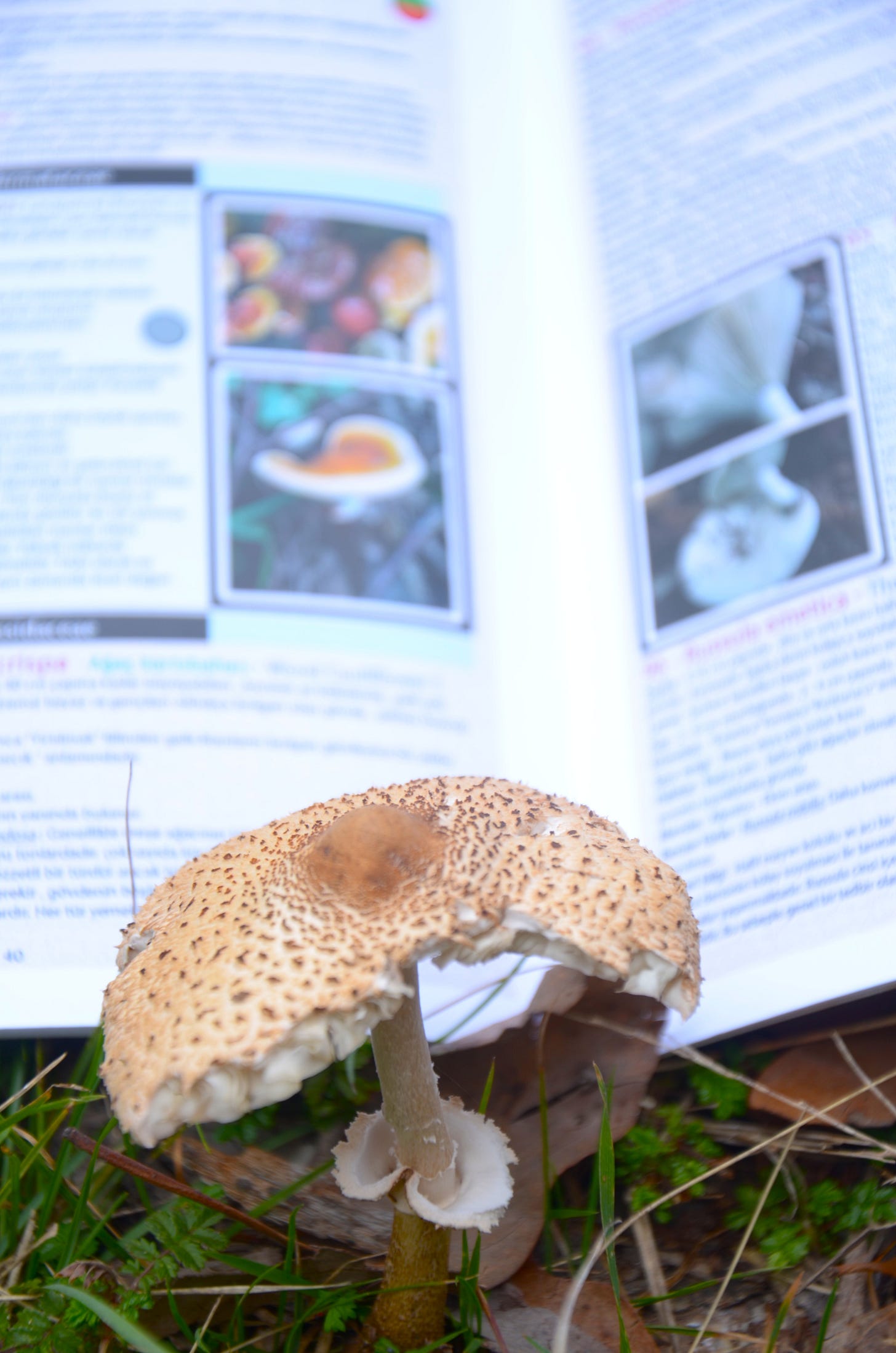

One of my treasured items is a field guide for the mushrooms of Turkey, gifted to me by my mate Roni Aran. Roni is a mycologist and a musician – we collaborated on a storytelling production in 2020 and he has a band called Fungistanbul that uses recycled items for their instruments and costumes.

Roni is one of the most interesting people I’ve met. It didn’t surprise me when I found out, rather later than you might think, that he’d written a fungi manual. It is not totally useful in my neck of the woods, but you may be aware that I’m a fan of mushrooms in all forms. And besides, I plan to return to Turkey someday – hopefully to go on a bushwalk with Roni – and it may be that I fly this little field guide half-way across the world once more so that I can put it to use in situ.

Books and places get stitched together in my memory. This is not only the case with reading material on international travels. There’s a bar in Launceston in which I was reading Eyrie by Tim Winton; I got sunburnt reading Robert Dessaix’s Arabesques outside a Tasmanian mountain hut.

Sometimes a tangled timeline forms. I might remember, for instance, that something happened in 2019, because I was living in a particular house – which I’ll only know with confidence because I can recall reading a certain book (let’s say it was a collection of short stories by Clarice Lispector) at the breakfast table.

I read The Merchant of Venice while in Paris, waiting for a Tasmanian mate who never showed up. (Or rather, she did, but hours late and I’d finished the book and walked away.) I had W.G. Sebald’s The Emigrants as my companion in the tent on a rainy camping trip in Scotland and during a lengthy hike in Iceland, I picked up Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang.

With such tangled links between words, history and environments, is it any wonder that I will put myself through the hard yakka of travelling with books?

Last year, I came down from a long trip into the Fann Mountains with a dry-bag full of finished books. Things were close to desperate – Tajikistan is not a country famous for its bookstores and the nearest city was a regional hub, where almost nobody spoke any English. It would be like to trying to find Persian books in Launceston.

I spent a night at a Soviet-built alpine retreat, a sort of base camp for mountain adventures that has since become a curious holiday destination for Russian tourists. An odd place, but I hadn’t slurped on a beer for about two weeks and it had a bar, so I was content. As I peered around the room, I saw a tiny library. My eyes swiftly scanned the titles and saw a surfeit of Cyrillic, as expected. But then I had a second look…

In the middle of the shelf was an English translation of The Eighth Life, a 1000-page tome by the brilliant Georgian writer Nino Haratischwili. In truth, I hadn’t read any of her work yet – I had been searching for her writing, always looking for her unmissable surname in second-hand bookstores near and far. It was a compact soft-cover edition and already dog-eared – a perfect thing to find to help me finish off my tour in that part of the world.

A similar thing happened here the other day too. Nearing the bottom of my literary barrel, I went down the road to a café that I’d heard recommended. The coconut coffee was yummy but even more welcome was the sight of a healthy book-swap. The pickings were rich, too. I gave up a couple of the books I’ve been carrying around and traded them for a mouldy copy of Banana Yoshimoto’s Kitchen and an edition of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass.

It won’t be long until I need another book-swap, but for now, it’s a relief to have enough reading material.

As for machine learning, I’ll brush up on that in another country, some other day.

I too have abibliophobia. And I love that there’s a word to describe the fear of running out of books. Imagine my joy when I found a copy of the Philosopher’s Doll by Tassie writer Amanda Lohrey at a book swap in Carcoar, NSW last week. It saved my life!

I was about to recommend a (dreaded) kindle while you’re travelling & hardcopy at home, but then I read on & realised it’s also about the searching and the finding and the serendipity. So I reckon - continue as you are!